But what's async anyway? (stackless coroutines)

But what’s async anyway?

Intro

Imagine a simple program whose job is to periodically send requests to server1 and server2. The delay before the next request is determined by the previous response; if you stop sending, your computer will blow up. How could it be implemented? Naively, like this:

def send_to_server(addr):

time_before_next_request = 0

while True:

time.sleep(time_before_next_request)

resp = http.request("GET", addr)

time_before_next_request = int(resp.data)

def main(addr1, addr2):

send_to_server(addr1)

send_to_server(addr2)

Why this approach fails

Looks fine and your computer is safe, isn’t it?

Not at all, because first send_to_server will

single-handedly occupy the whole thread of execution forever and you’ll

never reach the second call! It’s definitely

not something great, and we must find a new solution. You could

think about using several threads of execution

(and it’ll definitely work), but I can show you a way of reaching the

same goal within a single thread.

A naive async solution

If you know some Python, you might immediately come up with such a beautiful solution:

async def send_to_server(addr):

time_before_next_request = 0

while True:

await asyncio.sleep(time_before_next_request)

resp = http.request("GET", addr)

time_before_next_request = int(resp.data)

async def main(addr1, addr2):

join = asyncio.gather(

send_to_server(addr1),

send_to_server(addr2)

)

await join

asyncio.run(main())

Remark: Notice that this code is still not truly asynchronous, because http.request blocks the thread. We’ll fix that in a moment. For now, let’s stick to this implementation.

If you are looking at this masterpiece of a syntax construction and already regret that you’ve opened this post, stop. It will become clearer in a moment. And even if you’ve come up with something like that, you might not fully understand what it means and how it is implemented, so let’s talk about it!

Building intuition

The goal of async

So, let’s first think about what we want from our code. The obvious goal is

“One function should be able to work while another is sleeping.”

But our functions have variables with the same exact name! Won’t this

variable be overwritten? Or even the argument addr! To avoid this

kind of stuff, we can save the state of a function each time

we think that other functions have time to be executed (we

mark these places with the await keyword):

{

function_name: "send_to_server",

next_line: 4,

variables: {

addr: <some_server_addr>,

time_before_next_request: <some_value>,

},

}

Introducing the runtime

Okay, our function’s states are safe, but how will we know when

some function should be called? We have a finite amount of tasks

that should be continued at some point, and each of those has the same

priority (if you miss a request to any of the servers, your computer

won’t live long), so that sounds like a loop! Also, we have some

“system state,” not only state for each function, so let’s call

this state runtime:

class Runtime:

tasks_ready_to_continue: List[(int, func_state)] # some id + state

timers: List[(time.time, (int, func_state))] # when should end + which task in

... # <some functions, that we will use later and which are trivial>

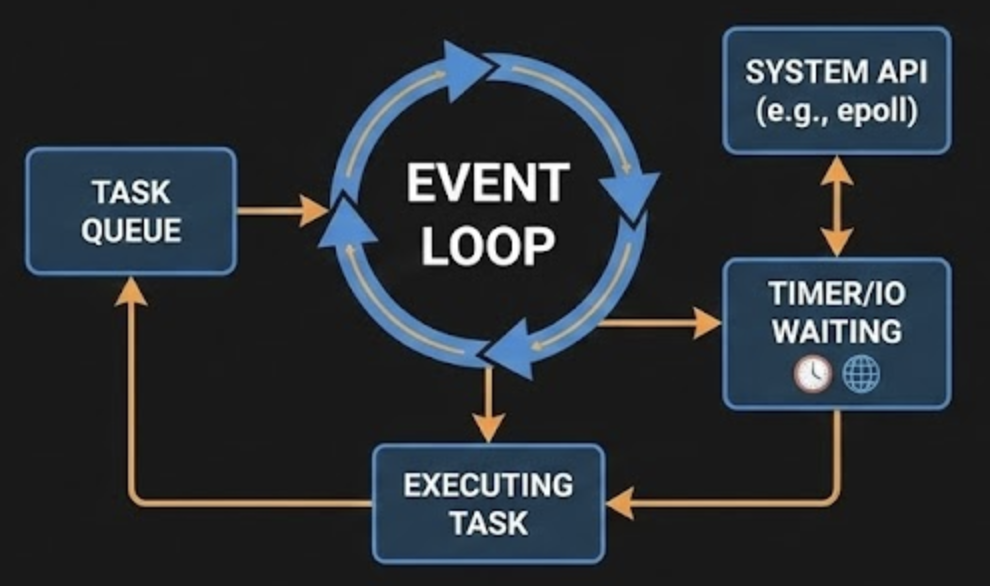

Designing the event loop

And now, as we have Runtime, let’s try to design our own loop!

Remark: basically, when we use

await, the function saves its state and “jumps” to the loop

while True:

# this loop is often called **event loop**!

# continue all tasks that we can right now!

# (but only one at a time, because single thread)

while runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue:

task = runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue.pop()

runtime.continue_executing(task)

# but what if there are no tasks?

closest_timer = min(runtime.timers)

time_left = closest_timer[0] - time.now()

time.sleep(max(0, time_left)) # thread can sleep without hesitation

timers = []

while runtime.timers:

timer = runtime.timers.pop()

if time.now() >= timer[0]:

runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue.append(timer[1])

continue

timers.append(timer)

runtime.timers = timers

The problem with blocking calls

This solves the ‘sleep’ part, but we still have a problem:

the HTTP request itself is blocking. While http.request is

running, the whole thread is stuck and no other coroutine can

make progress.

So, we should add await to the HTTP request like this, right?

async def send_to_server(addr):

time_before_next_request = 0

while True:

await asyncio.sleep(time_before_next_request)

resp = await aiohttp.request("GET", addr)

time_before_next_request = int(resp.data)

Supporting non-timer events

But our loop (for now!) has no way to work with non-timer events.

In Linux, there exists an API called epoll

(MacOS has kqueue and Windows has IOCP, which do

practically the same). You can think about it as a structure

that can store some amount of

files (a socket that we use in an HTTP request is a file too!) and

answer a question: “Which of these files are ready to be read from

or written to?”. The function answering that question is

called epoll_wait. You don’t need to understand how epoll is

implemented, just remember what its function is.

Finalizing the event loop

Now, with that in mind, let’s add support for non-timer operations!

while True:

while runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue:

task = runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue.pop()

runtime.continue_executing(task)

closest_timer = min(runtime.timers)

time_left = closest_timer[0] - time.now()

# when we can read from a file, epoll returns some "event" that

# includes a previously specified value. let's assume that we've

# specified (task_id, state) for each non-timer operation

events = []

# also, let's assume that epoll already has necessary files

# epoll wait returns the number of files that can be interacted with

n = epoll_wait(epoll=runtime.epoll,

events_list=events,

timeout=max(0, time_left))

if n == 0:

# timer was earlier than any file was ready

timers = []

while runtime.timers:

timer = runtime.timers.pop()

if time.now() >= timer[0]:

runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue.append(timer[1])

continue

timers.append(timer)

runtime.timers = timers

continue # as no files need any interaction with

for ev in events:

runtime.tasks_ready_to_continue.insert(0, ev.data)

epoll_remove(ev) # as we already got what we wanted

When async is useful

And that’s the final version of our event loop! It handles multiple

tasks at once, can work with timers, and keeps your computer safe in

case of a very specific and unrealistic problem that almost certainly

won’t ever happen in your life! But there are some cases when async is really needed:

- Web servers that get many requests at once. Threads are good, but threads that can handle multiple requests at any time are cooler!

- Database access in your app (they’re relatively slow too)

- Background processing of external programs

- Many other things

Function coloring problem

If you’ve read carefully, you might have noticed a problem: await

can be used only in an async function, because any other function

doesn’t have a state that is saved somewhere. That means you can’t

await an async function from a normal function. Once some function

needs await, it usually has to become async too, and this can

propagate through your codebase. This phenomenon is called

function colouring, which exists across

multiple languages and is a design choice, not a bug. Wonder how

you can deal with it? Accept.

Conclusion

Obviously, our implementation of the event loop is not ideal. It lacks

proper error handling, is not very optimal, and doesn’t include the implementation

of a real-world state machine for functions, etc., but I hope the process

of building it gave you some intuition about how async in Python, Rust,

JavaScript, and C# is implemented (this model is called stackless

coroutines). async makes the compiler store functions’ state somewhere, and await saves it for the caller and jumps to

the event loop where it waits for the next event.

And also, that’s not the only way of implementing concurrent execution, but that’s a theme for another post :)

Thanks for reading!

Read more about it

by miko089